by Brett Kelly

“In the Country of Women is moving, fierce, and gorgeous. In a time of individualistic fragmentation and the tearing of the social fabric, Straight offers the contrary narrative, the essential need for community, its past and future, and celebrates her place in its weaving.”

—Janet Fitch, author of White Oleander

“In the Country of Women is a masterpiece and a great read—heartfelt and soul-warming. A full life, cleanly, deeply, and beautifully told.”

—Dorothy Allison, author of Bastard Out of Carolina

“In the Country of Women must be the most populated, celebratory, filled-with-life memoir of our time. With her characteristic mix of compassion, warmth, humor, and acerbic insight, Susan Straight writes of her ‘massive black and mixed-race family’ and her ‘quirky, deeply embedded white family’—a memoir that is, though addressed to her three daughters, a valentine to virtually everyone whom the renowned author has known in the course of her vividly described life. Unlike most contemporary memoirs, which focus upon singular, self-obsessed individuals, Susan Straight’s is about an entire way of life, lived with great verve and passion: ‘a strange California transcendentalism which never fit in with American upward mobility.’”

—Joyce Carol Oates

“In the Country of Women is the astonishingly beautiful story of a life and family history that could only happen in California, just as California is a place (and an idea—of expansion, light, color, a meeting of bloodlines and cultures) that could only happen in America.”

—Attica Locke, author of Bluebird, Bluebird

I just bought a car for my oldest daughter, who is sixteen. A red Honda Civic, circa 1994, with only three dents. She and I were impressed by the chrome rims, but when we brought it home, our neighbor corrected us with a laugh. They’re hubcaps.

Cheap ones.

My ex-husband, Dwayne, helped out physically and financially. We checked out the car together, where it was parked in a dirt backyard not far from where we grew up. After we examined the dents, we both glanced at the pepper trees and then squinted at each other. Even though we have been divorced for eight years, we knew the other’s thoughts: Didn’t we party in this yard, during high school?

We did.

This is southern California. Cars figure in nearly every memory of our lives together in the same city where we were born. In fact, for the most part my ex-husband doesn’t remember names, but connects friends and acquaintances with their vehicles. He’ll say to me, “I saw your old friend today. The one used to drive the Duster.”

“Ah,” I’ll reply. “Julie.” She drove a Duster in 1978.

He’ll say to our three daughters, “Call that one girl – her grandma drives the Escalade.”

Our daughters are very good at recognizing makes and models of cars and trucks. They know the difference between Blazers and Broncos without hesitation.

My father taught me to drive on deserted vineyard roads. He’d raced cars as a teen in inland southern California, and told me stories of using a sewer pipe for a muffler to amplify sound. I practiced on his vintage 1965 Mustang, and when I swerved on a dusty road to avoid a ground squirrel, he shouted at me for the first time in my life. “Who’s gonna live – you or the damn squirrel! Don’t ever choose an animal over yourself.”

Dwayne learned on dirt roads, too, in borrowed cars. But when we began dating, he was just sixteen and I was fifteen. We walked for months to parks and burrito places, until his father broke down and bought The Batmobile.

The first time Dwayne drove up to my house, I couldn’t believe it. The car was a 1960 Cadillac, vintage oxidized brown like faded coffee grounds, with huge fins as if sharks were chaperoning us down the street. Sitting in the passenger seat, I saw a dark stain along the inside of the driver’s door.

It was cold, and I asked him to close his window, but he couldn’t. He didn’t want me to see the spiderweb cracks around the bullet hole in the glass. Then he told me the story of the car, while we headed to the movies. Some guy had been leaning against that car window when he was shot. The bullet pierced the glass; the man fell into the door and the dark stains were reminders of his blood.

“You went out in the Batmobile last night?” his friends teased me at school the next day.

“You let me go out in the Batmobile?” I said to my mother last night on the phone.

“What did I know?” she laughed.

Dwayne’s father had seen the car parked under a tree in someone’s yard, and knew the story. He kept asking the father of the murdered man to sell it, and finally the man relented. $200 was the price.

We never had much money growing up. But we do tell our girls the good-time stories we have, and they all involve cars. My stepfather bought a vintage 1965 Mustang from a barn, and the convertible top was gone while a hay bale filled out the missing back seat. During high school, no one wanted a ride home from me. Then he sold that and bought a 1959 Thunderbird, which I raced against our friend Wendell’s car, a Pontiac named Maybelline. Where the road narrowed to a bridge, he chickened out.

We cruised with eight bodies packed into our friend Penguin’s Dodge Dart, and when The Bar-Kays sang “Your Love is Like the Holy Ghost,” we all moved in unison so that the car leaped up and down without the aid of hydraulics.

One of our girls’ favorite stories is about our wedding. We got married downtown, and we had no limo, but after the ceremony, Dwayne’s cousin Newcat drove us around the local lake in his Cadillac, which had a broken horn. The best man, Dwayne’s older brother, shouted out the open windows to waving onlookers, “Honk, honk, damnit, these people just got married!”

Well, now we’re not married. But we both taught our daughter to drive. Her father counseled her to stay out of the bike lane. I reminded her not to drift into the left lane on a right turn.

I brought the red Honda home, and she drove with one or the other of us for a few weeks. The car drove fine, but it didn’t have a radio. I offered to have one put in, but Dwayne said he wanted to take care of it.

He got an inexpensive CD player at the local swap meet. When I came home from work that day, Gaila had her first car story.

“I was doing my homework and Daddy kept calling me with his cell phone.”

“Where was he?”

“In front of the house installing the stereo,” she said, rolling her eyes. “First he said, G, bring me a lighter. We didn’t have one, so I gave him some matches. Then he called again. G, bring me some tape. I brought the wrong kind twice. The silver tape and the white tape. He wanted that black one.”

“Electrical tape,” I said.

“Yeah. Then he said, G, bring me some water.”

I laughed. “You’re slow,” I said. “Didn’t you realize what your dad wanted?”

She shook her head.

I remembered our early days of marriage, our old broken down cars – a Fiat, a Renault, each of which required hours of Dwayne’s time under the hood. In our old gravel driveway, I used to sit in the driver seat with my own work, because every few minutes he would ask me to do something. “Start it up. Rev the engine. Push down on the brake pedal. Okay.”

Really, he wanted my company, and so I wrote most of my first book there, in the car.

“He just wanted you to sit out there with him,” I said.

She sighed. “Well, I had homework. Then he called me again and said, ‘G, listen.’ He turned the music up real loud and I heard Kanye.”

When I saw my ex-husband the next day, I said, “Thanks for the stereo.” He handed me a small silver figure with a clip. It was an angel holding a note that read, “Drive safely, Daughter.”

“I got this at the swap meet today,” he said. “Put it on the visor, okay?”

“I will,” I said.

When he left, he hesitated by the red Honda for a moment, and nodded his head.

I finished my seventh novel on New Year’s Day. After transcribing the tiny, cramped sentences I’d originally written by hand on a series of those subscription cards you find inside magazines, I wanted to sign off with the date, and then name the exotic locale or city considered an intellectual haven where I’d typed the final page.

Books have a certain literary cachet when authors sign off with Prague, Paris, New York City, Cape Cod, and Rome and mention writer’s colonies in Italy, Vermont, and Santa Fe. But I always tell the truth, when I’m not writing fiction, and so the most appropriate end note for me is Mercury Villager, Riverside, California.

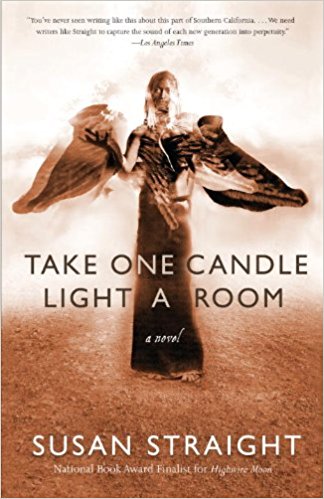

I wrote most of my new book, Take One Candle Light a Room, in my car. Longhand, on legal pads, on the backs of discarded homework papers from my daughters, and yes, on about fifty of those inserts from Runner’s World or Sport Fisherman (from the waiting rooms of doctor’s offices.) You have to write very small, around all the print on those things.

I tell my students – whether in college classes, prison workshops, or elementary school presentations – that anyone can write, anywhere, at any time, and I mean it. I bring my legal pads to show them. I have lived in the same house for 22 years, less than a mile from the hospital where I was born and two blocks from the city college where I wrote my very first short story, when I was sixteen, in a lined notebook like the one carried by Harriet the Spy.

I wrote my first novel Aquaboogie in a pale green 1975 Fiat parked in my father-in-law’s driveway, often while my husband was working on the vehicle. He would say, “Check the brakes!” from underneath the car, and I would push down on the brake pedal, then write a few more pages in my notebook.

After that novel was published in 1990, I was 29, and had a baby about to turn two, was pregnant again. My life seemed so circumscribed, and I fantasized, as many writers do, about the writers’ colony where I would have meals delivered silently to my porch while I typed in a room where only the sound of birds would break into my concentration. But I worked on my second novel while sitting on the curb, while my first daughter had finally fallen asleep in her stroller. I was hunched over my notebook, the stroller beside me with the brake on, when a car pulled up. A woman offered me money and sympathy, since she thought I was homeless.

I’m just writing, I said. She frowned. Writing what?

I couldn’t say it, back then. I knew I looked bad. Tired, wearing old clothes, holding a legal pad. A novel? Just writing, I replied. She shook her head and drove away.

This year, I tried to feel sorry for myself – but then I remembered a photograph of Eudora Welty, sitting with perfect posture at her desk in her bedroom in the house where she was born. I remembered an interview with Raymond Carver, who said that to escape the chaos of his home and family, he often wrote in his car, parked in front of the house.

I realized I was a native southern Californian who had spent much of her life in the car. There was an expansive freedom in the windshield, completely different from a house window. And my middle daughter was most like me – when we pulled up after school, everyone else went inside, but she and I stayed in the car while the sun was lowering, starting homework or just staring at the trees before the others came to get us, puzzled by that small liberty.

This year, while I worked on a novel about a travel writer who has never married or had children and who has refused for years to help her orphaned godson, my 20-year-old nephew came to live with me and my three girls. My nephew, who needed me in the past, and who I was afraid to take in, because it seemed too much. With his dreadlocks and skateboard and ONE LOVE tattoo, his Pan-like mischief, he has transformed our house. The constant laughter of visiting skateboarders and YouTube drove me to a familiar place – the van – where I wrote about the travel writer, a woman selfish and beautiful, with only coffee in her kitchen, rather than endless stacks of frozen pizza. Would she rescue her godson from the trouble that could get him killed?

Six yellow legal pads, the backs of letters, even day passes from Disneyland covered with words. I finished the novel at dawn during the rare night all the children spent elsewhere, typing ten hours without stopping except for coffee and chocolate. My brain went into a fugue state of imagination that might feel like a deserted cabin somewhere, a colony, so that I could write after the very last line something that sounded impressive and not the prosaic and common name of my village.

It seems like I’ve never gotten anywhere, but I’m cool with it now, I’d better be, and so I write – 2010, Riverside, California.

I just let the chickens out to play. We’ve been at work and school for most of the day, they’ve been cooped up (that’s where the word comes from – chicken coop) and the sun is shining. The hens are teenagers, but they are still cute, unlike many teenagers. They are six months old, one golden and friendly, one black speckled and wary. They are sisters, named Butter and Smoke.

They run around in the back yard, following me the way my daughters used to, when the garden was a daily-explored universe full of ladybugs and earwigs and pink jasmine blossoms and green apricots like fuzzy pieces of jade.

I am embarrassed to admit I feel tender and companionable toward two chickens.

And because within minutes our neighborhood hawk is circling above us, crying and warning and feinting in the wind, I can’t believe I’m babysitting. When we first put these two chicks in an old rabbit cage, one morning the hawk sat on top of the wire mesh, cocking his head. He’s been hunting these chickens for weeks now, but if I’m here in the back yard, he stays away.

I sit on a wooden chair and watch them scratch the soil. Every few minutes, the chickens run over to see if I’m still here. I turn over a paving stone and they eat an entire nest of slugs in about two seconds. Very convenient. My older daughters, 16 and 14, don’t come into the garden very often now, because of SAT classes and basketball, and they don’t even want to rake leaves, much less help me destroy slugs. Last week, I moved two wooden crates full of tools, and when black widows dropped from the slats and ran toward my toes, Butter snapped them up. (For a moment, I worried that she might be poisoned, but the spiders must have tasted good, because she looked frantically for more.) Kids can’t do that.

Even my youngest daughter, Rosette, who is ten and still loves the garden, often has homework. These are her chickens, but they are my odd company. Butter and Smoke come when I call them, as my girls used to, when I say loudly, “Look what we’ve got here,” and I move aside the birdbath. My girls used to have pillbug farms, and their Tonka trucks and bulldozers are still here, half-buried in the dirt.

But I can’t believe I’ve developed maternal feelings toward chickens during the years of avian flu, during the afternoons of hawks.

Recently I went to a lecture on avian flu and learned that backyard poultry could be the first place where this disease will gain entry to our population. (I also learned that influenza viruses are ingenious and lethal, can mutate from birds to swine to humans, and that the Spanish Flu which killed millions of people in 1918 was not from Spain, but began in Haskell County, Kansas as an avian flu, mutated through bird droppings consumed by pigs into a swine flu, and then was transmitted to American troops stationed there for training. The soldiers took the virus on ships to Europe.)

Tom Scott, an expert who spoke during the lunchtime seminar, believes the present avian flu virus, H5N1, will probably not travel to America through an infected wild bird. He showed us the migration patterns of this flu from Southeast Asia to Europe to Africa, a series of jagged routes running north to south. It looked the same as the pattern West Nile virus took throughout America, through mosquitoes and birds.

He, and other experts, don’t think ill migratory birds would make it across the Atlantic Ocean. They believe it will arrive on another winged carrier – an international flight, with an infected human.

But other experts believe birds will travel as usual from Asia to Alaska, bringing the virus to the Western United States, very soon. When migrating birds fly over southern California in great numbers, which they do every year to seek shelter in the desert at the Salton Sea, they could spread the virus through feces. Ron Farris, poultry expert at UCRiverside’s Cooperative Extension, told me I had better put the chickens inside a wood-roofed enclosed coop, and never let them out to be exposed to the wild.

I watch my chickens ruffle their feathers until they are bigger for a moment, like brief explosions of fringe, and then they settle down for their daily dirt bath. They like the moist soil near the rabbit cages, where they scratch out a shallow depression and open their wings to throw dirt onto their backs. That’s how chickens keep mites and bugs out of their feathers.

I had been feeling proud at my little utopia, my rabbit fertilizer which nurtures my corn crop, my corn cobs feeding the chickens, along with bugs I don’t want around anyway, and then the fresh eggs. But the chickens are pecking at the poop now. I have visions of influenza virus mutating into the rabbits, and Snowball, the meanest one, biting one of the girls.

Near my feet is a peanut hidden by our resident scrub jay, pushed into dead leaves under the geranium. Every day, I find pecans hidden by the crows, who always forget their stash. Usually, my girls and I consider this found treasure and crack them open on the spot.

But now I recall the viruses shown on the lecture-room screen, their mutation capabilities, and I see the bird poop on the fence, and on the birdbath.

“You have chickens?” people at work say to me, incredulous, frowning. “Actual chickens? You’d better get rid of them now. Haven’t you read Mike Davis’ book?”

I have.

“Why chickens?”

We’ve always had rabbits, and a dog. We have twelve rabbits now – they’re quiet, easy to play with, and they make great fertilizer.

But my brother lived for years on an orange grove, next door to a man from Chihuahua who raised fighting roosters. My brother loved to see the birds growing and trained, but he didn’t like the fighting part. He got a few roosters for himself, but only trained his favorite rooster to sit on the couch with him and watch Monday Night Football, complete with Doritos for their snack.

Rosette wanted a farm like her uncle’s, and so several years ago my ex-husband brought her home with a shoebox containing two day-old chicks. Oldest trick in the book. Cute babies, held by a cute kid.

I learned that there are few sounds sweeter than baby chicks getting ready to go to sleep at night, in the laundry room, in a tin washtub. It’s not peeping. It’s more of a strange little comforting song, directed at the sky turning purple, almost as if they were chanting to themselves what they’d done all day and what they planned to do tomorrow.

But my ex-husband doesn’t speak Spanish, and though he’d tried to convey his desire for hens at the feed store whose proprietors were from Mexico, when the chicks had quickly outgrown the tin washtub and been transferred to a large rabbit hutch, where we fed them warily but didn’t know what else to do, they began to crow. At five am.

I called him during his graveyard shift that night and said, “You’d better come get your roosters.”

I have to give him credit. He took them to his back yard, where they tortured his neighbors, whose dogs tortured him. The roosters crowed so loudly and constantly that we had trouble talking to Daddy on the phone.

Those dogs broke the fence eventually. But he bought two more chickens for us, insisting they were girls. Caramel and Fudge. We put them in a nice big coop, which was an old dog run, but they were still mean. Animals have personalities, and these females were mean enough to be on The Bachelor. Caramel ate her own eggs, which was just wrong. Fudge taught us the terms pecking order (we were last), henpecked, and you feeling peckish?

During the summer when West Nile virus hit hard in Riverside County, both chickens got sick. Fudge recovered, after losing her tail feathers, but Caramel languished for three days, getting weaker and weaker.

She was still a creature. I put her in a separate cage, as she didn’t try to peck me, and I put water and food near her beak. It was hot, and the earth was hard, and I knew she would die in the morning, when I would have to get ready for work, so late that night I soaked the ground near the old bunny graves, marked by river rocks. Then I dug the hole, in the dark.

My ex-husband called during his night shift to see how she was. When I told him, he was shocked, “You dug the hole and she could see you? Dang. That’s cold. At least move her around the corner.”

I said, “You’re the one who keeps bringing me chickens.”

“I bring them for Rosette,” he said.

I buried Caramel at dawn, and he brought Butter and Smoke, shortly afterward.

The other day Luis, an acquaintance from Corona, showed me how to hypnotize them. He lay Butter on her side while she struggled and squawked, and with a stick he drew a line in the dirt near her eyes, over and over, while murmuring, Hey, hey, hey.

He said, “If you do this right, they’ll just lie here forever, until you snap them out of it. I learned it on my grandma’s chicken ranch in Mexico.”

I watched Butter, who did look dizzy and limp. “But why?” I asked.

Luis laughed, and Butter ran off. “There was nothing else to do down there.”

I’ve tried it only once, but the motionless chicken made me nervous. I don’t want to dig holes for these two birds stepping contentedly around my feet right now. I know the interface between the larger world and my yard, between the urban and wild, is so permeable. I stay awake at night, hearing the skunk and possums lumbering through the leaves, thinking of the fleas that carry bubonic plague. I see the raccoon peer from the sewer drain across the street, and think of rabies.

Amid the garden of blackberries, beds for corn and tomatoes and zucchini, the chickens eat everything, even spider eggs and microscopic insects invisible to me.

And when I am out checking the beans, I remember that chickens are women’s provenance. (That’s where the term egg money comes from.) All over the world, women are throwing corn for hens, hoping hens will eat the grasshoppers decimating their plants, and surviving on the children of the chickens.

These have not laid eggs yet, but Fudge does, and I take today’s egg into the house. The teenaged chickens are on their own for now, because the girls are calling me.

At the sink, though, washing the large brown egg while my kids do their homework at the kitchen table, I wonder how avian flu will drift into my yard, my small postage stamp of soil in this huge map of the world.

Right now, the resident sparrows, a flock of ten or so that live in my mock orange hedge, are following the chickens around the yard. The blue jay is sitting on the fence. The hawk is gone, but he will return.

Because the sky is going lavender, the huge flock of crows begin their flight to the riverbottom pecan grove where they’ve lived since I was a child. For the seventeen years I’ve been in this house, they have flown over us in a long skein of trembling black, calling to each other. They were gone, that year of West Nile, and the sky was eerily silent.

I have the kitchen window opened, and I am listening. The girls squabble over lined paper and talk about boys who think they’re players. Above the sound of traffic on the busy four-lane avenue outside, and the dogs barking and car stereos thumping, I’m listening for the hawk. And when the cry comes, it pierces the air like a dart – the high keening register, the echo off the tallest palm trees, and I’m grateful. I hurry outside and put the protesting chickens back in their cage for the day. The hawk flies far above me, circling, dipping, riding the currents. The wind tosses the branches of the carob trees.

In the air above us now, predators wait patiently, and in the soil under us, viruses and fleas thrive. And yet there are still young hens and children and those of us watching, narrowing our eyes, only vigilance and hope to protect us.

“Susan Straight is a remarkable writer— there is no new, emerging voice of the past decade more exciting, more surprising, and more richly and subtly human than she.”

— Joyce Carol Oates

“A book by a writer whose love for her characters infuses her work with the dignity and urgency they so clearly deserve.”

— New York Times Book Review

“Rarely is a black community so precisely, humanly, and searchingly delineated.”

— Minneapolis Star Tribune

“A world of pain and love and longing is contained in these stories.”

— Los Angeles Times Book Review

“Straight’s portrayal of a black woman’s life is nearly miraculous in its astonishing richness of detail, its emotional honesty and its breadth of human thought and feeling.”

– USA Today

“Susan Straight opens up a whole world, which good writers do. In her case, however, it happens to be a world that many of us don’t really want to go to…It is a world where the language is often not lush but hard and rough as concrete.”

– Los Angeles Times

“Straight gives that Godforsaken area of Southern California back some of its natural beauty…This is fine writing, and fine now means something different as well, something sparkling and glamorous, but with a big-hearted integrity born of much suffering.”

– Los Angeles Times

“Her gallery of misfits reminds one of Flannery O’Connor’s– but with a dash of sympathy and human goodness.”

— The Washington Post Book World

“An eye-opener of a novel, a road map to the real California. Straight turns headlines into poetry.”

— The New York Times Book Review

“Packed with the kind of detail about people, places and emotions that transport the reader to a different world.”

— San Francisco Chronicle

“One of America’s gutsiest writers … a polyglot with an astonishing ear for how people really talk in places we hardly remember they are living.”

— The Baltimore Sun

“Radiant. . . . Unforgettable, a classic haunting story of love, tragedy and perseverance.”

— The Miami Herald

“Moving. . . . Lush passages drip like Spanish moss from Straight’s prose [she] writes with nuance and insinuating grace.”

— The Seattle Times

“Intelligent and heartbreaking. . . . Celebrates the individual’s power to create a personal freedom within the most rigid social order.”

— The Portland Oregonian

“It is only the rarest of novels that cry for a sequel, the most unusual of stories that at once satisfies and leaves the reader aching for more. Susan Straight’s remarkable Take One Candle Light A Room is such a novel. And she has satisfied our desires in Between Heaven and Here, a magnificent novel, that manages to be at once unflinchingly real and transcendently beautiful. Susan Straight is one of the very best American writers. If you haven’t read her, you’re in for a delight and an awakening. If you have, then you’re probably as thrilled as I am that she has taken us back to Rio Seco.”

—Ayelet Waldman

“Susan Straight finds LA’s secret heart in Between Heaven and Here and with a sleight of hand only the masters have, she creates an alley, a neighborhood, a history that is as rich and tragic as any Shakespearean tale.”

—Walter Mosley

“Straight employs glorious language and a riveting eye for detail to create a fully realized, totally believable world.”

—Kirkus (Starred Review)

“Beautifully-written narrative.”

— Kirkus Reviews

“Straight thoughtfully captures the 9-year-old girl’s ability to perceive her parent’s emotional struggles while dealing with feelings and questions of her own.”

— Booklist

“Readers will . . . be glad to see the quiet and persistent heroine rewarded not only with the love of a good dog but with the promise of a closer family.”

— The Bulletin

“In luscious prose, Straight expertly captures the complexities of Fantine’s identity.”

– Booklist

“A searing, ultimately redemptive novel about America’s legacy of racial violence and a woman’s struggle to forge her own identity…Straight writes about the thorny subject of race with sensitivity and nuance.”

– Kirkus (starred review)

“A vivid portrait of a mixed-race family, proud yet haunted by the vagaries of the past…Straight beautifully blends the rhythmic cadence of the Creole patois with the down-and-dirty slang of the street.” — Library Journal.

Cover Design by Toni Scott.